Preliminary work / financing / script

“This title would stay with me like a trademark for the rest of my life. In the beginning its success could not be anticipated, however a failure would also be interesting, said Günter Grass and prompted me to write a diary. I should just write down everything that happens, the usual ups and downs during the making of a film, nothing extraordinary, just our experiences, as unmasked as possible…” (Schlöndorff 2011, p. 242)

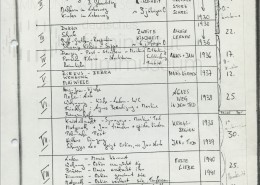

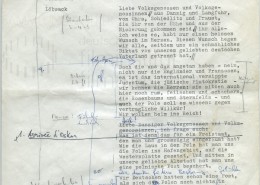

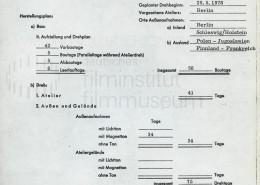

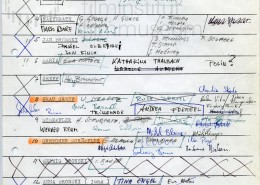

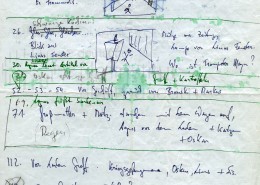

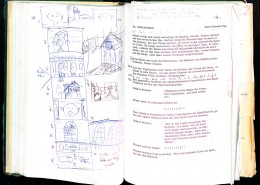

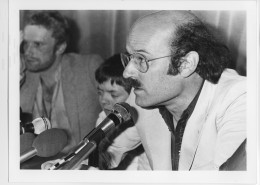

Schlöndorff actually kept a diary during the research and the production, filling four notebooks with his thoughts. They provide information about the process of the filming as well as the fears and hopes of the producer. His notations start with his first meeting with Günter Grass, their first ideas about production problems and obstacles in financing, up to the documentation of the individual shooting days:

7/7/78

I am petrified. Tonight I dreamed of the first screening of the Tin Drum film in Paris in front of about 600 guests. There was no reaction in the auditorium. During the last sequence, a re-appearance of Oskar as infant, who cautiously taps a waltz beat and starts dancing, the audience is already leaving the auditorium. When the lights go on there is already an atmosphere of departure. No word, no applause.

Schlöndorff’s film adaptation of DIE BLECHTROMMEL (The Tin Drum) is only dedicated to the first and second part of the narration, whereas the postwar years and Oscar’s life in the psychiatric hospital are left out. In Schlöndorff’s notes one finds his thoughts about a Part Two of the BLECHTROMMEL (The Tin Drum) which would take place in the 1950s, the time in which he himself grew up. The project remains unrealized to this day. (Schlöndorff 2011, 20. Oktober 77, p. 249)

After finishing the first script, written by the producer Franz Seitz, doubts arise at the film adaptation of the interlaced cut-backs and Oskar’s Off-texts. This draft which starts with the experiences made in the psychiatric hospital “were cumbersome and overpowered with information. […] Eventually we start with the potato field, the grandmother and the classic fairy tale entrance that says: ‘Once upon a time…'” (ibid., p. 249).

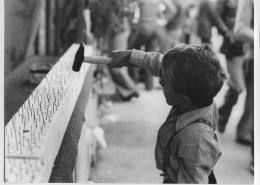

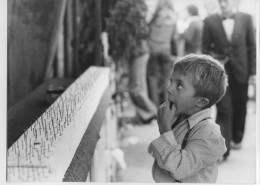

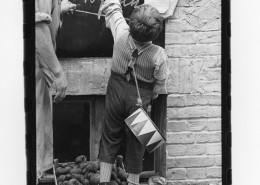

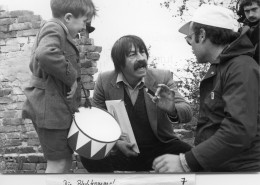

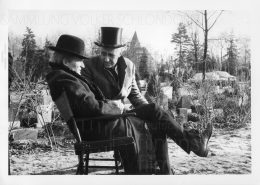

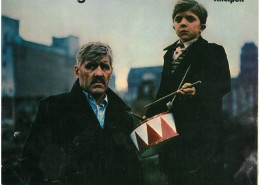

A further challenge brought the search for the right actor for the Oskar character. Schlöndorff and Seitz visited, amongst other things, a congress of growth restricted people and quickly agreed: “Oskar needs to be a child, and it needs to be as growth restricted as possible.” (ibid., p. 247) In the course of their research they visited doctors specialized in this phenomenon and discovered 12-year-old David Bennent, son of the actor Heinz Bennent, who played the character of the lawyer Hubert Blorna in Schlöndorff’s film DIE VERLORENE EHRE DER KATHARINA BLUM (The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum). After their first meeting at the Munich Oktoberfest Schlöndorff was sure to have found his Oskar Matzerath.

The work on the script was halted in November 1977 due to production problems. The production costs were estimated to be at least 6 to 7 millions DM. The consideration to shoot the film in English, with stars such as Dustin Hoffmann or Roman Polanski as Oskar and Isabelle Adjani and Keith Carradine as his parents, was quickly rejected. However, Schlöndorff was still distressed about the realization of his project:

16/4/78

The following difficulties bring me close to giving up:

The preparations are just a „fire drill”, as of a lack of definitive contracts there is no money for tests and employment.

The reception of the film is threatened by the lack of good technology, foremost special effects.

The contract negotiations will stay precarious until the last moment – right now, for example, UA (United Artists) jeopardized because of the resignation of Emet Goldschmidt, Berlin credit still not passed […], FFA [Filmförderungsanstalt] postponed.

No useable studio in Berlin.

Fear of staging a bourgeois environment because of the lack of own experience.

A film in German and in such a dimension cannot be amortized.

From June 6th on the financial aids get granted. The Berlin credit gets granted and on June 12th the commitment for the loan of the FFA over 700.000 DM. Finally the contracts can be signed: “Now the money is here. On the eleventh hour!”

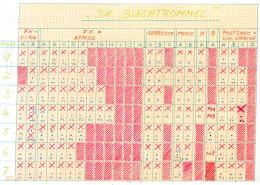

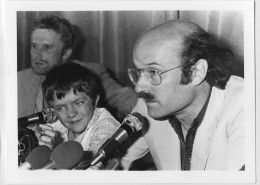

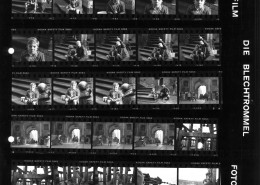

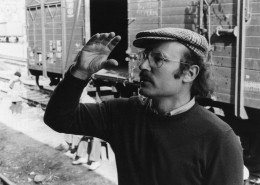

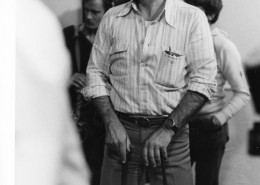

Shooting

14/06/78

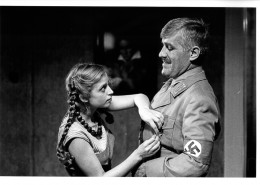

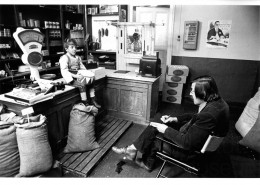

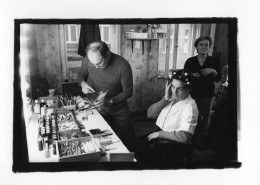

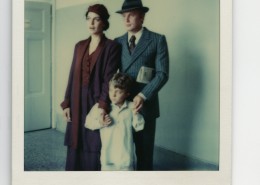

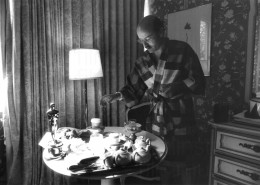

Today are the first test shoots. Yesterday, over the course of the day, David and Angela, Mario and Daniel arrived, as well as Mariella Oliveri and her mother from Rome – a charming Roswitha! In addition, the costume team from Berlin, makeup artists, etc. In the evening they are all at our place, and there is a great understanding between all of them. Mario makes Matzerath jokes, Angela and David are flirting, and a lot of wine and schnapps is being drunk. David has brought her a Kashubian mirror and gets himself adored by her. The relations are perfect. David walks from one of his presumed fathers to the next, cuddles and flatters Angela, marvels at the dark eyed, little Italian girl […]. It is almost eerie how well they harmonize. What a presumption to bring people together that way, to hand them over to their parts and relationships. Then again, how wonderful that everyone is able to settle in so well. They all look so authentic that it seems we are closer to a documentary than a literary adaption.

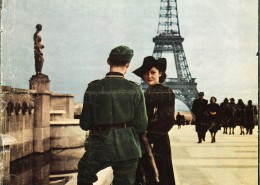

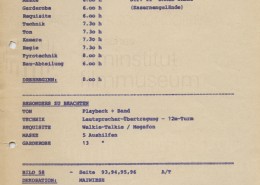

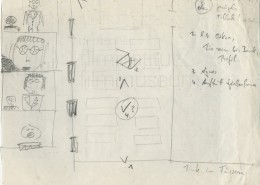

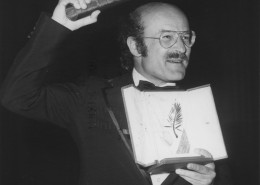

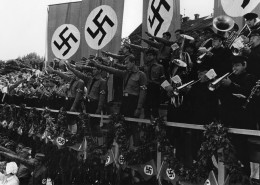

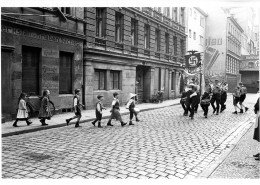

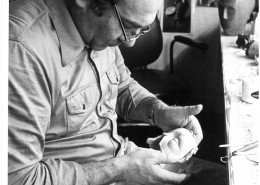

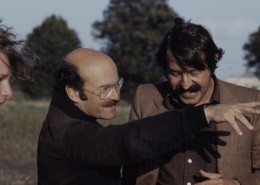

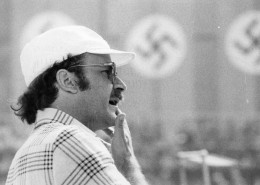

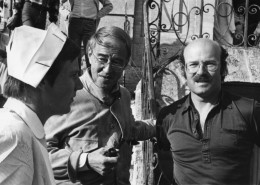

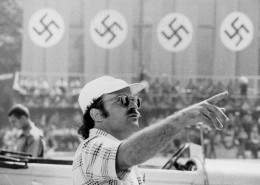

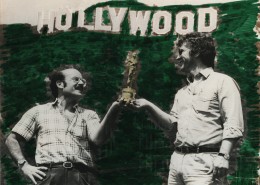

The complex special effects still were of major concern to the director and his team. The expert Georges Janconelli was brought all the way from Paris for his aid. He, together with Nikos Perakis, will work on the glass shattering by singing, the bomb explosions, shootings and other pyrotechnics, also with the help of uncommon techniques: “For the glass shattering by singing a sound generator from the Opel factory will be delivered”. (Schlöndorff 2011, p. 262) On 31 July 1978 the shooting began in Zagreb with the picture 58: May meadows. In November, after 17 weeks of filming and various other locations in Zagreb, the Normandy and Gdansk, Poland, the shoot is wrapped up in the CCC Studios Berlin. On 3 May 1979 the film launched in Schlöndorff’s hometown Wiesbaden and in Mainz.

Cast

“David wants precise instructions as defined by the Stanislavsky system – I hope we will always find them.”

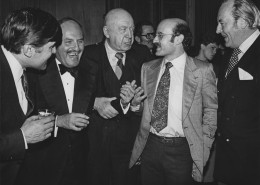

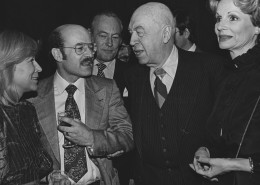

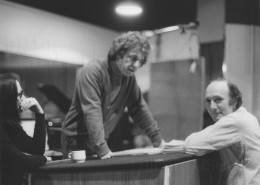

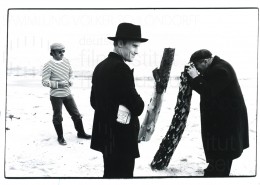

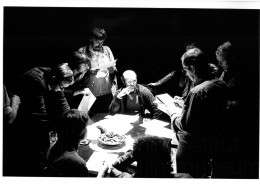

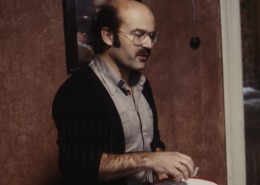

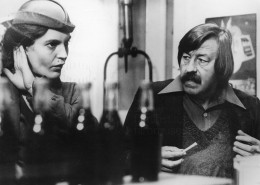

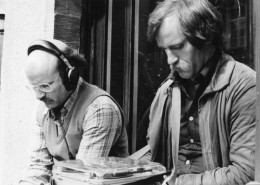

Günter Grass often met with the actors at the end of the day to speak with them about their roles. He gave his opinions about the reactions, motivations, and emotions of the figures, and made it clear why they act the way they do, and what is going on in the mind of the characters.

“I don’t understand explanations anyway. I just play what I read in the in the script, he says in his Viennese accent.” (Schlöndorff 2011, p. 287) – Fritz Hakl is an artist for more than 20 years at the time of the shooting. As a person with restricted growth he was unsuitable for the field work at his home farm, so he went to the Prater. David Bennent, in contrast, absorbed every information that he could get hold of. For Schlöndorff he was more than just an actor. “He is a medium. He has his own problems, similar to the ones of Oskar Matzerath, therefore he seems so authentic. He does not play Oskar Matzerath, he is Oskar.” (ibid., p. 288). The 25-year-old Katharina Thalbach too wanted to “‘play’ at every cost” and said about herself that she “can never get enough.” (ibid., p. 296)